™

™TRADITIONAL MOUNTAINEERING

™

www.TraditionalMountaineering.org

™ and also

www.AlpineMountaineering.org

™

™

™

FREE BASIC TO ADVANCED

ALPINE MOUNTAIN CLIMBING INSTRUCTION™

Home

| Information

| Photos

| Calendar

| News

| Seminars

| Experiences

| Questions

| Updates

| Books

| Conditions

| Links

| Search

![]()

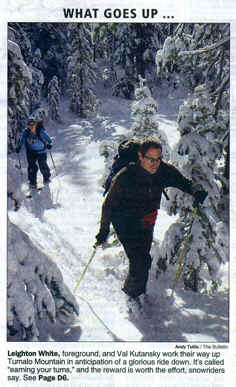

Tumalo Mountain a wintertime treat

The Bulletin

By Keith Ridler

December 30, 2003

Halfway up Tumalo Mountain on a clear day it's possible to pause and find an opening in the trees to look across the Cascade Lakes Highway with a certain smugness at

the snowriders flying across the slopes of Mount Bachelor.

You, after all, are in the midst of being your own chairlift, ascending on your own power.

Farther up the mountain when you pause somewhat more frequently to glance over at the fast-moving specks on Mount Bachelor, your smugness might give way to a bit of

envy.

But it is, after all, called "earning your turns" for a reason.

"It's a good hike," said Marcus Ciambrello of Flagstaff, Ariz., a former Central Oregon resident visiting during the holidays. He had hiked up on snowshoes and then ridden

his snowboard back down. "I was disappointed not seeing any other snowboarders this morning, though. I had to break trail all the way up."

Tumalo Mountain is, for many Central Oregonians, their first introduction to backcountry snowriding — a sport favored by those ranging from the cash-strapped to purists in

search of untracked powder.

Tumalo Mountain is a respectable 7,775 feet high, and easily accessible from Dutchman Flat Sno-park. Some backcountry snowriders also start out from Vista Butte

Sno-park. A sno-park pass is needed to park in either of the areas.

"It's one of the most accessible, and the bowl has a good pitch," said Terra Leven of Pine Mountain Sports in Bend.

Depending on an individual's fitness and mode of transportation, the trip to the top can range from under an hour to two hours. Skiers, either telemark or Alpine touring, and

aficionados of the split snowboard — all of which use climbing skins to provide traction on the way up — tend to be more efficient. A fair number of snowboarders use

snowshoes to hike up, while some simply walk up in their snowboard boots.

"I'd say it's a combination," said Leven. "Mostly telemark, but there are a lot of AT skiers up there, and I see a lot of snowboarders. There are also just a lot of snowshoers."

On Tumalo's east flank is the payoff — an expansive, steep bowl that offers a treeless powder run. Once at the bottom, snowriders head back up, if they still have the

energy, for another trip. Otherwise, it's time to point the skis or snowboard back toward one of the sno-parks for the run through the trees and back to the vehicle.

Visitors to Tumalo Mountain, particularly in winter, need to be self-sufficient, Leven noted. Unlike the Mount Bachelor Ski Area across the road, there is no ski patrol to

come to one's aid.

Also, there is no avalanche control on Tumalo Mountain, and the bowl on the mountain is considered prime avalanche territory under the right conditions.

"They don't happen a ton, but they still happen," said Leven, who has made the trip to the top more than once only to decide against skiing the bowl because of the

avalanche danger. "I've seen remnants and heard of folks getting caught in small ones."

The bowl is also prone to having a cornice of snow build up above it, a result of prevailing winds.

"It will build up a cornice," said Bob Speik, an experienced backcountry traveler and Web site author. "I've seen cornices nearly the size of a school bus up there."

In fact, with the recent snowfall and stormy weather, Leven said the bowl is best avoided for the time being.

"I wouldn't ski the bowl right now," she said. "That's an awful lot of snow to come down on you. And there are plenty of other good shots to do."

Those include the old growth glades, which from the top of Tumalo Mountain is a line that sort of aims toward the cone next to Mount Bachelor. Or there is the shoulder

along the bowl, which from the summit is on skier's left.

And there are other lines coming down through the trees back toward the sno-parks. The trees and brush help hold the snowpack in place, and that side of Tumalo Mountain

is considered much less prone to avalanches.

"And it's not as steep," Speik said.

Ciambrello made the trip up and down Tumalo with only his dog, snowboarding down the southeast side of Tumalo Mountain to the road, where he hitchhiked back up to

Dutchman Flat Sno-park.

"It's a little tougher (to hitchhike) with a dog," he said. "You've got to wait for a pickup."

Though Tumalo Mountain gets a fair number of solo snowriders, Leven recommends backcountry snowriders travel in groups for safety reasons and carry avalanche beacons

and shovels. An avalanche beacon can aid in finding someone buried in the snow.

Though alone, Ciambrello carried an avalanche beacon anyway because Tumalo Mountain attracts so many backcountry snowriders.

But the odds are against surviving an avalanche, either because of injuries caused by the avalanche itself or running out of oxygen before being dug out. Therefore, as Speik

and Leven said, the best advice is to avoid getting caught in one to begin with.

Leven recommends a book called "Snow Sense" ($8.95), which helps explain some of the signs to look for in an unstable snowpack. Also, Central Oregon Community

College offers several classes.

Pine Mountain Sports takes groups up Tumalo Mountain for free, and participants can take part in the digging of a

snow pit and examining the snowpack. The next trip is planned Jan. 18.

But Speik points out that studies have shown extra equipment and one or two classes can sometimes provide a false sense of security. That, combined with a lack of

experience in understanding snowpack dynamics, can increase the risk of getting caught in an avalanche rather than simply walking away from a potential disaster.

"Here's the thing," said Speik. "When you're a skier or snowboarder, that's what you do. You get on those slopes that may avalanche. So you're going have to except some

small degree of risk. But learning how to dig a pit and having all this gear is going to make you more likely to be hit by an avalanche. (Some snowriders) attempt to dig a pit

and make a decision that only an expert can make."

But even if the bowl is off limits for a while, that doesn't mean the rest of the mountain needs to be avoided.

"It makes for a wonderful winter hike up there," Speik said.

![]()

Read more . . .

Avalanche avoidance by David Spring

What can I observe

about avalanche risk on specific slopes?

Avalanche avoidance is a

practical approach to avalanche safety

A map of know avalanche areas near Bend, Oregon

Copyright© 1999-2003 by Robert Speik. All Rights Reserved.